BACK FROM THE BRINK

How Lake Ellwood, Once Doomed Is Being Rescued

By Eric Engbretson, Engbretson Underwater Photography

Imagine a town consisting entirely of seniors. The town has no children, no teenagers, and no young adults. All the schools, playgrounds, and sports fields have closed. The town is eerily empty and still. And every year, as seniors pass on, the town’s population grows smaller and smaller. With no young people to replace the departed, the town will simply disappear from the map. A grim future indeed.

Until last year, this same sad demise seemed destined for Lake Ellwood in Florence County, WI. In its waters, bluegill and largemouth bass had grown old. For the better part of a decade, no young fish were surviving to replace them. But now it seems that a corner has been turned and the news is good. Today, Ellwood is a lake on the brink of recovery. The story of the lake’s resurrection is a tale that involves invasive plants, a dedicated fisheries biologist, and a host of scientists working against the clock to save a small but beloved piece of Florence County.

THE CRASH

A healthy lake gets a steady stream of newborn fish every year, and the newborns that survive to maturity constantly enlarge the adult population. Fish biologists call this process recruitment. Of all native fish, largemouth bass and bluegill are both extremely prolific and they have shown outstanding talent for recruitment. Unlike walleyes, which require very specific conditions to reproduce, largemouth bass and bluegills thrive even when conditions are far less than ideal. Typically, when two years pass without largemouth bass and bluegill recruitment, fish managers become concerned, and Lake Ellwood has now seen seven consecutive years with failed recruitment. Dr. Andrew Rypel is the state’s lead panfish researcher for the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. “It’s an eyebrow-raiser to be sure. What’s happened on Lake Ellwood has gotten our attention. It’s very weird.”

Greg Matzke is the DNR’s senior fish biologist for Florence and Forest Counties. When I visited him in his office at the Florence Resources Center a year ago, he was eager to discuss Lake Ellwood. “The fisheries biologist position for Florence was vacant for three years prior to my arrival,” he told me. “By the time I got here in year 2010, many of our lakes hadn’t been surveyed in a while. When we got around to looking at Lake Ellwood in 2012, the fish population hadn’t been surveyed for a decade. What we found was a lake with few young fish. By the end of our spring survey it was clear to me that something was wrong with some of the major fish populations in Lake Ellwood.” What Matzke documented in 2012 was an almost total collapse of the fish community. In Wisconsin, a failure of this magnitude in largemouth bass and bluegill recruitment is utterly unprecedented.

Matzke typed excitedly on his keyboard as a graph flashed onto the screen. Compiled from the data he had collected, the graph showed a sudden drop in northern pike recruitment after 2004, followed by bluegill and largemouth bass recruitment failures after 2006. Northern pike and largemouth bass recruitment had not occurred at all since 2004 and 2008 respectively, while bluegill recruitment fell off and became insignificant after 2006. “We surveyed that lake extensively, with 44 fyke net lifts and 7 complete electrofishing surveys totaling 20.22 miles (on a lake with 2.8 miles of shoreline) and couldn’t find a single fish younger than five, six and eight years of age, for largemouth, black crappie and northern pike. Not one.” said Matzke. “Nobody has ever seen anything like it.” In total Matzke spent 19 days surveying the fishery in one small lake, which is a great deal of time and effort, and I wondered how many lakes earn such scrutiny. “Not many,” said Matzke. I asked the big question: “What happened to the fish?” He paused and exhaled. In a reflective mood, he lowered his voice: “At first I had no idea, but after gathering and analyzing all the data it’s quite clear…. I believe it has to do with the milfoil treatments out there.”

THE MILFOIL CONNECTION

In the bars of Spread Eagle, fishing is a hot topic among the locals. It fills the air in the summer months, when local businesses are booming and lakefront owners are spending more time on the water. Between rounds, someone mentions the fish crash in Lake Ellwood, and explanations flow like beer from a freshly-tapped keg. On a steamy night last July at the Chuck Wagon Restaurant, the fate of the lake engaged almost every person in the room. Barroom biologists blamed culprits ranging from low water levels to fish cribs and even invasive Eurasian watermilfoil (EWM) sucking the oxygen out of the lake.

Back in their offices, Matzke and his colleagues considered these possibilities and decided none of them were credible because these same conditions exist on hundreds of lakes throughout Northern Wisconsin, and none of the lakes has shown collapses in fish as was documented in Lake Ellwood. In their opinion, the crash stemmed from chemical herbicides applied to control the invasive plant Eurasian watermilfoil.

Eurasian watermilfoil (EWM) was discovered in Lake Ellwood in 2002. Treatments started during the next spring. The Lake Ellwood Association contracted with a lake management firm to monitor and treat the lake every spring thereafter with very good success. As chemical treatments continued, invasive plants began to subside. Encouraged by their success, the lake association continued treatments in the hope of eradicating small but persistent areas that would materialize. An unintended consequence was that native plants were also being killed by the herbicide.

Once considered the most crucial problem facing the Lake Ellwood Association, milfoil has now taken a back-seat to the lake’s most urgent issue: The fish crash. It was a shift in priorities that took time to embrace. Matzke recalls that “when it came to Lake Ellwood, too many people were focusing on the wrong thing. In the beginning, when I told them about the fish crash, they listened, but still seemed more concerned about the milfoil. I explained that milfoil was not the biggest problem. A milfoil-free lake is worthless as a fishery if it can’t sustain healthy fish populations.” Many people were still talking about invasive species ruining the lake when it was losing its fish at an alarming rate. “We needed to do something to encourage fish recruitment before it was too late.” Despite being alerted to the collapse of the lake’s fishery and a hypothesis that linked the crash to the milfoil treatments, in the spring of 2013, the Lake Ellwood Association applied for their annual permit to continue chemical treatments. The news of the disappearance of what was once a balanced, self-sustaining, and vibrant fish community had seemingly fallen on deaf ears. Matzke, along with WDNR water regs staff, denied the permit application. He defended what was an unpopular decision at the time by saying, “We need to take a time-out and find out what’s going on in this lake. It’s not a stretch to suggest that the milfoil treatments may be doing more harm than good.” At first, many were unconvinced that any connection existed, but since then, those who have studied the data compiled by Matzke admit that the evidence is hard to ignore.

So how could treatments aimed at invasive plants be hurting Lake Ellwood’s fish? The exact pathways behind the crash are still being investigated, but two plausible reasons might explain why multiple fish species have failed to recruit. One is that the chemicals disturb the aquatic insect community that young fish need for survival, and the fish literally starve to death in their first few months of life. Another theory that holds more water is that the chemical herbicides have depleted too much of the lake’s native plant community that young fish need for refuge. Without dense plant beds to hide in, young fish may be preyed upon by larger fish, and by the fall, entire year classes of fish are gone with no survivors to contribute to the lake’s fish community. It could also be a combination of both of these scenarios. While it’s unknown exactly how the fish crash happened, it’s clear that the chemicals played a key role. Native vegetation is critical to fish. There are many examples illustrating this important connection. On other Wisconsin Lakes, the loss of native vegetation has proven to be the cause behind similar crashes of largemouth bass and bluegill populations. In those lakes, rusty crayfish or common carp were responsible for removing too much native vegetation, causing largemouth bass and bluegill populations to collapse. On Lake Ellwood, the same thing has happened. But on this lake, humans, using herbicides, are behind the loss of native plants fish need.

Dr. Andrew Rypel, Wisconsin’s leading panfish researcher, says that the complex relationship bluegills have with plants are just beginning to be understood by fish scientists. “We’re trying to understand how this occurred and we’re looking at other water systems with aquatic plant management programs around the state to see if this is an anomaly.” He added, “With bluegills, we know habitat is important. In fact, for the first time, we’re really starting to study how plants affect fish quality”.

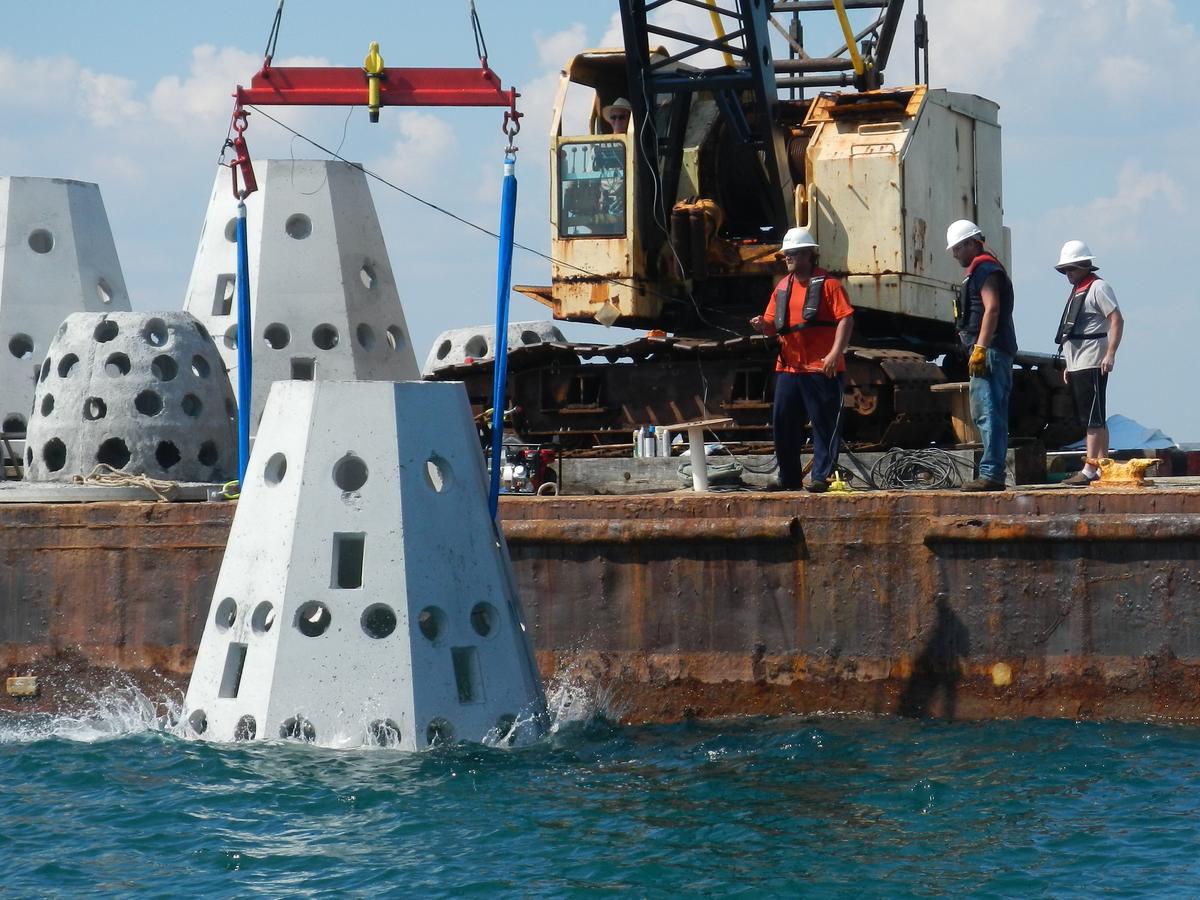

Is there a way to save the fish, preserve native plants and still limit invasive milfoil? “Yes,” says Greg Matzke, “But not with continual use of chemical herbicides.” Denied permits to use any further chemical herbicides, the Lake Ellwood Lake Association cleverly looked to alternative methods of milfoil removal. Last summer, they contracted with an Iron River company, Many Waters LLC, to use Diver Assisted Suction Harvesting (DASH) as an alternative to herbicides. The DASH system features a giant vacuum cleaner atop a pontoon. At the bottom of the lake, scuba divers use their hands to pull out invasive milfoil (and avoid native plants) and then feed it into a tube that takes it to the surface for collection and removal. Unlike chemical treatments, DASH acts selectively by focusing only on milfoil and leaving other plants generally undisturbed. Matzke gave his warm approval to DASH: “We need to preserve and expand native plants in Lake Ellwood for fish to have a chance at survival. The DASH system removes milfoil without harming the native vegetation essential to fish.” Early results appear encouraging: In the summer of 2013, DASH took more than two thousand pounds of milfoil out of Lake Ellwood.

HOW BAD ARE INVASIVE PLANTS?

Dr. Jennifer Hauxwell is chief of fisheries and aquatic sciences research at the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. Headquartered in Madison, her team of scientists have been studying Eurasian watermilfoil for ten years. What they’ve discovered so far is that EWM is tough to pin down. It doesn’t seem to behave in any two lakes quite the same way, and there’s no way to predict if it will peacefully co-exist with native plants as it does in most lakes or reach overabundance as it does in others. Hauxwell says, “In some lakes EWM never ‘takes off’ or expands to levels requiring any management. In some lakes EWM is a major component of the ecosystem and may provide structure/habitat complexity if native species diversity is low or absent. In some eutrophic to hyper-eutrophic lakes EWM may be the only species keeping the lake from turning to algae dominated.” Hauxwell says her team has found other cases where it’s proven beneficial. “Lake Wingra, once suffered from murky water due to algal blooms and lots of suspended sediment”, says Hauxwell. “When carp that root up sediment were removed from the lake, the water cleared, and light was available to support plant growth. EWM quickly expanded in the lake and helped further clear the water and keep algae and suspended sediment low. It’s now a recreational nuisance, but it’s definitely playing an important ecological role in the lake community.” Currently, EWM occurs in 4% of Wisconsin’s lakes mostly in small colonies that are not problematic. “Our researchers quantified the amount of EWM in approximately 100 EWM lakes to get a sense for how widespread it may be in any given lake and across different lakes.” Says Hauxwell. “We found that there was a wide range in abundance. In the majority of the lakes we studied, it was sparse and occurred in less than ten percent of the inhabitable zone.” When does it reach nuisance level, I wondered? “’Nuisance’ is very difficult to define, and it’s in the eye of the beholder”, says Hauxwell. Her team is excited about a plethora of research studies currently underway that will shed even more new light on this enigmatic species.

Mike Vogelsang is the DNR’s fisheries supervisor for the Woodruff area and oversees all fish management in six counties in Northern Wisconsin, including Florence. He’s more concerned with the chemicals used to control EWM than with the invasive plant itself. “There’s some real questions by our biologists, since they’re the ones required to review, and ultimately approve chemical application permits. What are the effects of chemical use going to be twenty years down the road? We’re already finding that in some cases they don’t break down as quickly as believed-they have toxicity long after the manufacturers say they do.”

Vogelsang also says that because it’s expensive to control and impossible to eradicate, learning to live with milfoil is inevitable. “Where are we really going with these treatments? When do they become excessive? What effects are they having on fish communities? These are some of the questions we’re talking about now.” Vogelsang isn’t satisfied that EWM is the destructive threat that’s worthy of all the resources directed to control it. “When EWM first came on the scene, there was a lot of fear associated with the plant, because it was a new potential threat, and the Department wasn’t sure if it would negatively impact our waters. To help stop its spread, there was a lot of gloom and doom talk with lake associations and the general public. We heard all these things about exotics and how bad they are, but it hasn’t been the end of the world. The sky didn’t fall. In many lakes, fishing got better with the invasives. I’m not saying exotics are a good thing – and we should do everything we can to prevent their spread – but EWM hasn’t impacted our fisheries.”

Is an unwarranted level of fear driving lake associations to respond too aggressively to milfoil? If so, it’s a fear that today feels like an over-reaction to a plant that now doesn’t seem to be capable of ruining lakes after all. Ironically, while EWM hasn’t harmed fisheries, the unintended consequences of using chemical herbicides to control it has, as it did on Lake Ellwood. Is what happened on Lake Ellwood an indictment of chemical herbicides? “When over-used, I think so.” Says Vogelsang. “It’s simple: No weeds equals no fish. If I had my own private lake and it got milfoil, would I attempt to control it with chemicals? No. I would leave it alone and know that eventually the plant would become naturalized with the native plant community – like it has on many lakes where no chemical treatments have been used.”

Steve Gilbert, another fish Biologist, echoes Vogelsang’s observations. He reports that for the past 22 years that he’s worked in Vilas County, the negative impacts of EWM on fish in Vilas County lakes has been zero.

While the DNR has consistently denounced EWM, new plant science and testimony from fisheries managers now seem to undercut the agency’s long-standing rhetoric. The days of demonizing Eurasian watermilfoil may be nearing an end. Stated simply, EWM is not be as bad as we formerly thought. It’s a tough bell to un-ring and DNR insiders are struggling to navigate the complicated path to this more moderate public position, without undermining their credibility.

THE FISH RETURN

May 2014. A year has passed since my last meeting with Greg Matzke and I’m back in his office to discover what has happened with Lake Ellwood since we last talked. The spring of 2013 was the first year in a decade when chemicals weren’t applied and the results were instant and dramatic. Grinning now, Matzke tells me that his fish surveys from the fall of 2013 show an astounding thirteen-thousand percent increase in young-of-the-year bluegill since 2012 (the last year of chemical treatment). The 2013 survey also found young-of-the-year largemouth bass, which makes the 2013 year class the first successful recruitment of this species in Lake Ellwood since 2008. In fact, largemouth bass recruitment in 2013 was measured at a rate more than double the recruitment level in 2002 (before chemical treatments began). This immediate rebound adds solid weight to the theory that herbicides did indeed cause the famous collapse in the fish community. A thirteen-thousand percent increase in bluegills sounds incredible and I asked Matzke to put the numbers into context. “We captured just over 97 age-0 bluegill per mile during our electrofishing survey; this is up from less than one age-0 bluegill per mile in 2012. The 2012 year class still looked poor with only 0.67 age-1 bluegill per mile during the 2013 survey. For the first time in a long time, conditions are acceptable for bluegill and largemouth bass to reproduce successfully. And they’re responding.” Putting the question as directly as possible, I asked if it was simplistic to think that “no plants equals no fish” and that “with plants, we have fish.” Matzke said, “That’s an interesting point. I mapped out the aquatic vegetation in Lake Ellwood during August 2013 with acoustic equipment to get a picture of the plants.” Showing me a multicolored map of the lake, he pointed to red-shaded areas that contained the most concentrated areas of plants. “We didn’t find a dense plant community by any means, but in certain near shore areas, there was dense plant cover where there hadn’t been any before.” Matzke draws an optimistic conclusion: “This suggests that for bluegill and largemouth bass recruitment, overall plant abundance may not be as important as these narrow strips of dense aquatic vegetation that are now found in Lake Ellwood after the herbicide treatments have stopped. These areas serve as great nurseries for young fish, offering preferred prey items and cover from predatory fish, giving bluegill and largemouth bass a fighting chance to recruit.”

When news of the Lake Ellwood fish crash started to spread, says Matzke, “I started getting calls. Other fish biologists from around Wisconsin, Michigan, and Minnesota had heard about Lake Ellwood and they were looking for more information.” They were consulting Matzke to learn about signs of incipient problems in their own lakes. Matzke also took “calls from regular folks around the State” who lived on lakes with invasive milfoil and who worried that chemical treatments were hurting fish populations in their waters. Was the same thing happening to other lakes? Matzke shrugged: “It’s really hard to say. To know for sure, you need to steer your sampling efforts to target young-of-the-year panfish. That’s not something fish managers typically do in their ordinary work. Unless you’re specifically looking for it, it’s the kind of problem that could go undiscovered for a long time and may go unnoticed until the adult population begins to be effected, as it did on Lake Elwood”.

Now retired, fisheries biologist, Bob Young oversaw Florence County Lakes from 2000-2007. He fondly remembers Lake Ellwood as once being a high quality panfish lake. He’s been following the recent changes closely and feels another important lesson can be learned. “The invasive species folks should be working closer with fish managers so they can avoid situations like this. I’ve always been uneasy with the notion that total chemical war needs to be made on any and all invasive plant populations. Maybe it wasn’t the best thing for Lake Ellwood.”

A PROMISING FUTURE

Events in Lake Ellwood have also drawn the attention of the Dr. Greg Sass. Sass is another member of the DNR’s elite Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences Research Section. As the agency’s equivalent of a CSI unit, these fish detectives answer calls to solve the most perplexing mysteries in the fisheries of the State. They’re the team whose groundbreaking scientific work in many areas over the years have directly led to major improvements in Wisconsin’s fishing. Sass visited Lake Ellwood in 2013 to investigate and define the forces behind the crash in the fish community. His ongoing study will gather more data not just from Lake Ellwood, but from two other lakes (Cosgrove, and Siedel) in Florence County. Sass is hopeful that eventually his team will be able to mechanistically explain the bluegill and largemouth bass recruitment failures observed in Lake Ellwood.

In Florence, meanwhile, Matzke says his office will continue fish surveys to monitor the recovery now underway. He remains optimistic about the future (which doesn’t include any further chemical treatments for Eurasian watermilfoil.) “It’s my hope that we can come to a clear understanding of the things that drive natural reproduction of the fish in Lake Ellwood.” Turning to the crash in the fish community, Matzke expressed his hope that “we can plausibly explain how the fish community crashed. So far the signs are quite clear; it was the treatments to eradicate milfoil—not the milfoil itself—that have seemingly indirectly caused the collapse in fish recruitment.” Lake Ellwood still has a few acres of invasive milfoil and likely always will. But native plants as well as young bluegills and largemouth bass are beginning to return. For fishery managers, that makes for a tradeoff with the sweet taste of victory.

Let’s go back to that town you imagined, the place where every citizen was a senior. The place is turning robust, as a new cohort of kids has taken to the playgrounds, sports field, and schools. “That’s not the same as a town with a lot of young adults,” cautions Matzke, “but it makes for a promising start.” At this time, the Wisconsin DNR’s careful work seems to justify the same spirit of cautious optimism about the future of Lake Ellwood. More habitat articles at fishiding.com

(For further information, questions or comments about this article, please email Greg Matzke at Gregory.Matzke@Wisconsin.gov)